![]()

|

|

DEMENTIA AWARENESSCERTIFICATE COURSE

UNIT FIVE |

|

|

COMMUNICATION AND DEMENTIA |

|

|

Introduction |

So far, we have considered what dementia is, the nature and quality of care required and the importance of considering communication when working with people with dementia. This Unit will focus on the interventions that can be utilised when working with people with dementia. In achieving this learning outcome you will explore your own perceptions and experiences of working with people with dementia and their carers, and comparing these to theories, research and current legislation that specifically addresses dementia care. This will involve, firstly, examining our own values that underpin our practice (because what we think and feel are reflected in what we do). Then, specific interventions will be analysed and evaluated in relation to specific areas; namely, cognitive impairment and functioning, non-cognitive symptoms of dementia, and, finally, emotional pain and palliation. These areas follow the discussion within the NICE/SCIE (2007) guidelines on the evidence-base for interventions.

Let’s begin with an activity that will enable you to begin to consider the types of intervention that are employed with people with dementia.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.1: QUESTION |

From reflecting on your own practice, what interventions are typically utilised with people with dementia?

What is the rationale for their respective use?

The NICE-SCIE (2007) considers interventions specifically in the following contexts:

Interventions for cognitive symptoms and maintenance of function

Interventions for non-cognitive symptoms and behaviour that challenges

Interventions for co-morbid emotional disorders

Palliative care, pain relief, and care at the end of life

|

|

Therapeutic Work: Values and Beliefs |

“Few areas of nursing care are as subject to the values, beliefs and attitudes of individual nurses as is the area of working with elderly people with dementia” (Pulsford 1997: 704)

In previous units we have considered various conceptualisations of dementia, and explored what is meant by person-centred care. In the introduction to this module, you conducted a values clarification exercise that considers some of your own values, beliefs and attitudes that, as a consequence, will inform your practice. In his review of therapeutic activities for people with dementia, Pulsford (1997) makes a pertinent point by prefacing his discussion with an acknowledgement of the importance of the practitioner’s own viewpoint. He asks questions that need to be considered, such as:

How do you regard people with dementia?

Who are we most concerned to help?

What are our goals?

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.2: QUESTION |

Answer Pulsford’s (1997) questions for yourself:

How do you regard people with dementia?

Who are you most concerned to help?

What are your goals?

We have seen in Unit Three the effects on care for the person with dementia dependent on our own beliefs and attitudes (as exemplified by Tom and Claire (Dewing 2007)). Pulsford (1997) offers some possible answers to the questions listed above, and notes some of their implications. Firstly, with regard to our views about the person with dementia, we could regard them as:

“people like ourselves”

“ex-people”

“people with a disability”

Each of these attitudes will have an implication for therapeutic work. For example, if the person is like us, then we may give them activities that we would do. The problem here is the effects of failure on the sense of well-being of the person with dementia. If they are “ex-people”, are we likely to engage in Kitwood’s (1997) malignant social psychology and adopt “malignant positioning” (Sabat 2001)? If so, the net results for the person with dementia could be an exacerbation of their condition. Finally, if they are people with a disability, then we may be more inclined to consider carefully what activities we promote, dependent upon their level of ability.

This is not just the result of our internal processes; there is also some evidence that the external context of our work has an effect on our attitudes and values. Skog et al (2000) found that nurses working in three different dementia care contexts learnt different things:

In day-care they adopted an appreciation for human dignity and learnt to see the person (the individual perspective)

In a group-dwelling context they learnt to appreciate the need to individualise care related to types and severity of dementia (the disease perspective)

In a nursing home context they focused on organisational and management issues, and staff attitudes to care (the staff perspective)

However, this is clearly not a universal occurrence. With regard to individual perspective, CSCI (2009) have shown that not all services display aspects of “personalism” (that is, care being given that the people themselves require). Concerning “the disease perspective”, Packer’s (2000) question: “Does person-centred exist?” is still not answered in the affirmative in all environments (AS 2007). Finally, the effects of staff shortages and issues around caring for people with dementia in these contexts have an impact on the quality of care (O’Kell 2002).

Secondly, Pulsford (1997) posed the question pertaining to the focus of our therapeutic work. Often, our answer would be the actual person with dementia. Clearly, putting the person at the centre of our therapeutic work is an ideal we would all applaud. However, as Unit Three’s discussion on relational care has shown, there are other people who may also need to be considered when working therapeutically, such as the main family carer(s). This has clearly been a neglected area, and has led to practical movements (such as the development of Admiral Nurses) and political changes (such as the necessity of conducting an assessment of need on carers under the Carer’s Act 2004). However, and perhaps more negatively, we may have as the focus ourselves – staff shortages and limited resources may necessitate a task-orientated approach to care that focuses more on the completion of tasks than on the therapeutic engagement of the person with dementia and/or their carer(s).

Finally, Pulsford (1997) asks about the goals of our respective approach to care. If, for example, we desire to maintain the person with dementia in their own home for as long as possible and/or maintain their respective level of functioning, then the goals of our work will be different from those where we desire merely to maintain the person’s quality of life – the difference being between what Pulsford calls “restorative” activities versus “enjoyment”.

Clearly there is a link between a person’s attitudes to therapy and the goals that they seek to attain. In order to evaluate the outcomes of a therapeutic activity, the goals need to be explicit. Pulsford (1997) notes in his review of therapeutic activities for people with dementia several outcomes that are related to the values we hold as practitioners. These are:

To enhance mental state or reduce/arrest mental decline

To reduce behaviour problems

To improve quality of life

To enhance staff morale and attitudes

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.3: QUESTION |

Reflect on your own practice and the therapeutic work you carry out with people with dementia.

Why do you do what you do?

Did any of your answers to the above question reflect Pulsford’s (1997) categories?

Specifically, did any of your rationales reflect his category of: “To enhance staff morale and attitudes”?

“To enhance staff morale and attitudes” seems a strange goal upon first reading. Surely, our rationale should be the person with dementia – not ourselves. Yet, Pulsford (1997) has already noted some of the issues with regard to how we view the person with dementia, and questioned whether they should be our only concern. It is worth noting in full what Pulsford (1997:707) states about this goal:

“It is sometimes suggested that the real benefit of therapeutic activities for people with dementia lies less in the activity itself than in the indirect path of enhancing the morale, attitudes and personal knowledge of their patients by care staff, with consequent improvements in the overall care that patients receive. Reality orientation and reminiscence have been particularly cited as having this benefit (Schwenk 1981; Jones 1988). It could be argued, of course, that it should be unnecessary to impose therapeutic activities that may have no intrinsic value on residents simply to achieve a quality of care from staff that should be there anyway.”

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.4: QUESTION |

What do you think about what Pulsford (1997) writes concerning the value of therapeutic work lying in improving our own morale and attitudes?

There are several points that arise from the Pulsford (1997) quote cited above. Firstly, although the perceived rationale is to improve our morale and attitudes, this is achieved by means of getting to know the person better and, as a consequence, improving the quality of care we give. This raises the ethical question: does the end justify the means? (a utilitarian perspective that will be discussed more fully in Unit Seven). Secondly, he cites some sources to substantiate his point. Schwenk (1981:374), for example, argues that:

“it is not clear whether RO is therapeutic for the staff or the elderly”.

There is some support for the notion that reality orientation benefits both family carers’ mood (Douglas et al 2004) and staff’s knowledge of the individual person (Patton 2006). As Holden and Woods (1995:132) note:

“Sometimes, interventions have to be developed in situations where carers’ and patients’ needs are discordant … approaches which fail to recognise them are likely to run into difficulties”

Finally, Pulsford (1997) asks the question: Is it ethical to carry out a therapeutic intervention that has no benefit for the person with dementia themselves? In this era of evidence-based practice, this is an important consideration – both professionally (being accountable for your own practice) and ethically (to be discussed in unit seven).

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.5: QUESTION |

Consider the code of practice for your particular profession (for example, the NMC Code of Conduct for nurses and midwives in the United Kingdom).

What does it state about your practice with regard to your therapeutic work with clients?

By way of illustration for the above activity, the NMC (2008) states that a nurse/midwife should:

Make the care of people your first concern, treating them as individuals and respecting their dignity

Work with others to protect and promote the health and well-being of those in your care, their families and carers, and the wider community

Provide a high standard of practice and care at all times

Be open and honest, act with integrity and uphold the reputation of your profession

It is clear from these broad statements, that the nurse or midwife needs to ensure that they act in a professional manner, and that the care they give “promotes health and wellbeing” and is of a very “high standard”. It also states that, firstly, you should “make the care of people your first concern”. As such, there is a need to ensure that our practice is person-centred and is evidence-based. We have considered the former of these in a previous unit (Unit Three: Care). Here, we shall consider the latter, namely, the evidence-base that should underpin our practice.

NICE/SCIE (2007) gives practitioners guidance on what interventions should be utilised with people with dementia in order to improve both the process and outcomes of care. They are clear to note that these are guidelines only. By this, they mean that they can:

Provide up-to-date evidence-based recommendations for the management of conditions and disorders by health and social care professionals

Be used as the basis to set standards to assess the practice of health and social care professionals

Form the basis for education and training of health and social care professionals

Assist service users and carers in making informed decisions about their treatment and care

Improve communication between health and social care professionals, service users and carers

Help identify priority areas for further research.

However, NICE/SCIE (2007:40) state explicitly that:

“Guidelines are not a substitute for professional knowledge and clinical judgement”

Their utility is limited by such factors as:

Availability of high quality research evidence

Quality of methodology used in developing guidance

The generalisability of the research findings

The uniqueness of individual people

For the practitioner, there must to be a consideration of two interrelated factors:

A need to critique research in order to inform practice

A need to practise utilising both research and one’s professional knowledge and clinical judgement

The former could be referred to as the “science” underpinning your practice; whereas the latter could be referred to as the “art” underpinning your practice.

This section will now consider the interventions proposed by NICE/SCIE (2007). These are divided into two types:

Therapeutic interventions for people with dementia – cognitive symptoms and maintenance of functioning

Therapeutic interventions for people with dementia – non-cognitive symptoms and behaviour that challenges

It also considers more specific interventions, such as:

Co-morbid emotional problems

Pain relief

Palliation and End-of-life care

There is also consideration of the wider family context:

Interventions for carers of people with dementia

With the exception of the last (which will be discussed in Unit Six), these will now be covered in turn.

|

|

Therapeutic Work: Cognitive Symptoms and Maintenance of Functioning |

This section will consider methods of working with the cognitive symptoms of dementia and the means by which functioning can be maintained.

Maintaining Functioning

“Health and social care staff should aim to promote and maintain the independence, including mobility, of people with dementia.” (NICE/SCIE 2007:24)

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.6: QUESTION |

Reflect for a moment on the quotation from the NICE/SCIE (2007) guidance.

In what ways does the care you and/or your organisation give to people with dementia “promote and maintain… independence”?

In Unit Four we discussed the signs of well-being for a person with dementia. These offer a useful guide to ascertain whether or not the person with dementia we are caring for is having his or her independence promoted and/or maintained. If they are not, according to person-centred theories advocated by Kitwood (1997), they will be in a state of “ill-being”.

|

Table 5.1 Signs of Well-Being and Ill-Being (Kitwood and Bredin 1992) |

|

|

Well-Being |

Ill-Being |

|

Being able to assert own will and desire Being able to show a range of emotions including pleasure and sadness Initiating contact with others Having self respect Enjoying humour Showing pleasure Being able to relax Being helpful |

Distress Despair Intense anger Physical discomfort Pain Fear Anxiety |

So, how do we “promote and maintain independence”?

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.7: QUESTION |

Consider a care plan you have written for a person with dementia. When considering their respective problems:

What interventions did you advocate to address their needs?

In what ways did these interventions “promote and maintain independence”?

NICE/SCIE (2007:24) states that:

“Care plans should address activities of daily living (ADLs) that maximise independent activity, enhance function, adapt and develop skills, and minimise the need for support. When writing care plans, the varying needs of people with different types of dementia should be addressed.”

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.8: QUESTION |

When considering your own care plans, ask yourself, in what ways do they:

Address activities of daily living?

Maximise independent activity?

Enhance function?

Adapt and develop skills?

Minimise the need for support?

Care plans should always include a number of things. With regard to interventions, they should be:

Individualised: for example, being flexible to accommodate the fluctuating abilities of the person with dementia

Supportive: allowing the person with dementia to progress at their own pace and engage in activities they enjoy

Specialised: referrals to specialists for their input are important (for example, ADL advice from occupational therapists, physical exercise advice from physiotherapists, and medical advice for problems with continence)

There is also a need to consider the environment in which care is occurring:

Are there stable and consistent staffing levels?

Is the physical environment familiar to the person with dementia?

Do modifications need to be made to facilitate independent functioning for the person with dementia?

The goal of all of this is to promote independence.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.9: QUESTION |

Read section 7.2 of the NICE-SCIE (2007) full guidance.

Make notes on ways in which independence can be promoted.

In what ways can these be accommodated within your own practice?

Facilitating independence is important throughout the dementia illness trajectory. This is partly because it is what all professionals working with dementia should aspire to, namely:

“Though the level of independence will change with the stage of dementia and other illnesses, a balance across personal care and productive, leisure, social and spiritual activities is important for quality of life and well-being.” (NICE/SCIE 2007:165)

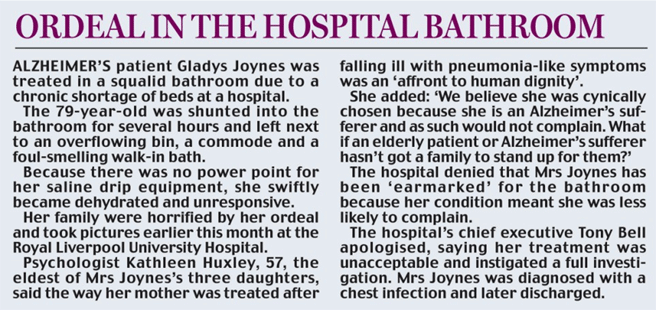

Although a vague concept to define precisely, surely anyone working with people with dementia desires to maintain a sense of quality of life and well-being, irrespective of the stage of the illness they are at. In one newspaper, the following story was noted:

Figure 5.1: Ordeal in the hospital bathroom

(Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1128682/The-NHS-really-IS-ageist-say-half-doctors.html)

In this story, the person with dementia is believed not to have a quality of life worth promoting and, according to the story, the family view this as a result of the patient simply being unable to speak up for herself (the ethics of this will be discussed in Unit Seven).

Another reason why promoting independent functioning is important is because research has shown that the level of functional deterioration is not commensurate with the level of cognitive impairment alone (Tappen 1994; Beck et al 1997). As such, it could be argued that “doing nothing” is tantamount to abuse (Crump 1991).

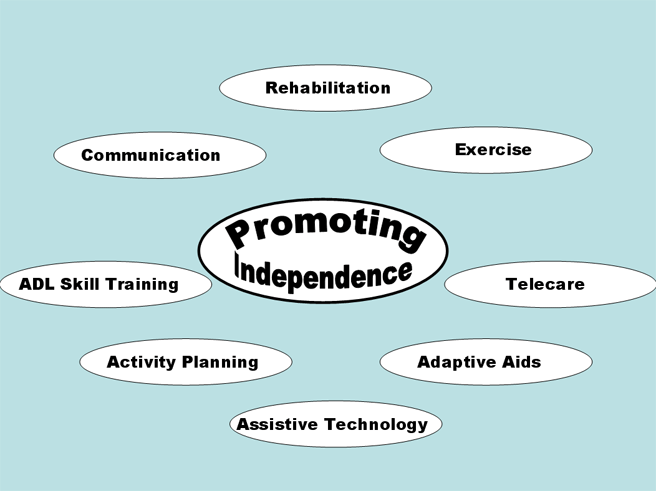

The NICE/SCIE (2007) guidance gives several suggestions on how independence can be promoted. Although it acknowledges that the evidence is not conclusive, it outlines suggestions for best practice.

Figure 5.2: Promoting Independence

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.10: QUESTION |

Select one of these areas of best practice as noted by NICE/SCIE (2007).

Conduct a literature search to ascertain the evidence-base for such an intervention for people with dementia.

Compare your conclusions from your review with the findings of NICE-SCIE (2007) and note especially:

Any similarities

Any differences

Give an explanation for your answers.

As has already been noted, dementia is an illness that affects many domains, not just cognition. As such, it is important to realise that, often, a multifaceted approach to promoting independence will be utilised. For example, Gitlin et al (2003) conducted a study that considered the effects of the “Environmental Skills-Building Programme”. This was an initiative to support caregivers who were providing the main care for people with dementia. It comprised several elements:

Information for the carer (e.g. effects of environment)

Problem solving techniques (e.g. ABC approach to challenging behaviours)

Technical skills to modify the home

They found that such a multifaceted approach had a positive effect on the carer which, in turn, was beneficial to the person with dementia.

|

|

Pharmacological Interventions |

Cognition

Anticholinesterase Inhibitors

The rationale for the usage of these drugs is based on the cholinergic hypothesis of dementia. This is a biological view of dementia and states that:

“acetylcholine is an important neurotransmitter in brain regions involved in memory. Neurons of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in the basal forebrain manufacture choline acetyltransferase which is transferred to the synaptic ending where it, in turn, manufactures acetylcholine for release into the synapse. Loss of cells in the nucleus basalis in AD results in a presynaptic deficiency in acetylcholine in areas of the brain involved in memory, including the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and amygdale” (Mendez and Cummings 2003: 560)

The theory is that if the levels of acetylcholine can be increased in these areas, then memory functioning can be increased as well. The first of these drugs to be licensed in the UK was donepezil in 1997. This was followed shortly after by galantamine (in 2000) and rivastigmine (in 2003). Initially, the NICE (2001) guidelines stated that they could be used for people with Alzheimer’s disease in mild – moderate stages of the illness (that is, those with a score on the MMSE of 12 or above) under the following criteria:

The person must be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and must be assessed for likelihood of compliance to medication

The treatment should be started by a specialist, but may be continued by a GP

The carer’s views about the condition should be sought before and during drug treatment.

There should be regular assessments of the person with dementia (every two to four months) after the maintenance dose is established. The drug should be continued only if there has been improvement in:

The MMSE or no deterioration (ie MMSE = 12 or above)

Behavioural or functional assessment

However, the MMSE has been noted not to be sensitive enough to measure improvements whilst on these drugs during clinical trials (Mendez and Cummins 2003). As such, other measures such as ADAS-Cog (Talwalker et al 1996), CIBIC-Plus (Joffres et al 2000) and ADCS (Cummins et al 1994) have been utilised in studies. They have been found to be beneficial for people with Alzheimer’s disease. For example, without medication, the person with AD declines about 6 - 12 points on the ADAS-Cog every year of the illness (Stern et al 1994). By taking these drugs for six months, they score better than those not taking medication (by 3.3 points on the ADAS-Cog on average) and experience significantly less deterioration on the CIBIC-Plus (Rogers et al 1998a; Wilcock et al 2000). As a consequence of taking these drugs, the person with Alzheimer’s disease can experience:

Modest improvement in cognitive functioning (Rogers et al 1998b)

Decreased progression of the dementing process (by six months in one-third of patients and one-half of those in mild-moderate stages)

Temporarily stabilised ability to feed and dress themselves (Tariot et al 2000

Improved mood (e.g. apathy, anxiety) and behaviours (e.g. neuropsychiatric problems (Mega et al 1999)

The improvement in functioning is perhaps most beneficial to carers and the person with dementia as it delays institutionalisation and improves sense of well-being and quality of life (Mendez and Cummings 2003).

However, in light of this evidence, NICE (2007b) reappraised the evidence and stated that these drugs were only to be used for people with Alzheimer’s disease who had a MMSE of 10-20 (that is, moderate dementia only). As such, it was no longer recommended for use with people in the early stages of the illness.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.11: QUESTION |

What are some of the implications of this decision for people with dementia and their carers with whom you work?

You may wish to make notes on some of the debates and findings of the NICE (2007b) technological appraisal. The document can be found at:

http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA111fullversionamendedSept07.pdf

Controversy surrounded this change in the guidance to the extent that the Alzheimer’s Society took NICE to court. NICE (2007b) acknowledge that the decision was not based on clinical effectiveness but on cost effectiveness. The utilising of the QALY measure was also controversial. Indeed, Sir Michael Rawlins (2008), the chair of NICE, acknowledge some of the limitations of this measure but stated that, until a better one emerged, they would continue to use it.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.12: QUESTION |

Complete the following table to ensure that you are aware of correct dosages and possible side-effects from this class of medication.

|

Drug |

Dosage |

Contraindications |

Side Effects |

|

Donepezil |

Starting Dose?

Max. Dose?

|

|

|

|

Galantamine |

Starting Dose?

Max. Dose?

|

|

|

|

Rivastigmine |

Starting Dose?

Max. Dose?

|

|

|

You may consider consulting the most recent British National Formulary for information about drugs. This can be found online at:

Hogan et al (2008) provide a useful summary of the information regarding dosages, contraindications and side-effects. Their review of the literature even suggests the number of people experiencing a particular side effect.

|

Table 5.2 Most Adverse Common Side-Effects (Hogan et al 1998) |

|

|

Donepezil |

Nausea 11% Diarrhoea 10% Headache 10% Insomnia 9% Pain 9% |

|

Galantamine |

Nausea 17% Dizziness 10% Headache 8% Injury 8% Vomiting 7% |

|

Rivastigmine |

Nausea 37% Vomiting 23% Dizziness 19% Diarrhoea 16% Headache 15% |

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.13: QUESTION |

Consider clients you work with who are prescribed any of these antidementia drugs.

Do they experience any of these problems?

How are they interpreted? As side-effects of the medication or as symptoms of the dementing process?

Memantine

Memantine was licensed in 2002 and acts on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors to decrease the amount of glutamate, a possible cause of nerve damage – a symptom of dementia. At present, it is the only drug licensed for the severe stages of dementia. However, as the NICE (2007b) do not recommend its use as a treatment except as part of well-controlled clinical trials, it will not be discussed here.

Other Medications

Section 7.5 of the NICE/SCIE (2007) guidelines lists some other potential medications for the treatment of dementia:

Natural Remedies (e.g. Ginkgo biloba)

Antioxidants (e.g. Vitamin E)

Anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. indomethacin)

Ergoloid mesylates (e.g. Hydergine)

Nootropic medication (e.g. Piracetam)

Vasodilators (e.g. Naftidrofuryl)

However, their review of the research literature did not recommend their usage. For example, it notes that the adverse reactions experienced by taking vitamin E, nimodipine, folic acid and indomethacin outweighed any therapeutic benefits for people with dementia.

Risk Factors

Other dementias, such as vascular dementia, have known risk factors that may precipitate their onset (Stewart 2008). In section 7.6 of their medication review, NICE/SCIE (2007) state that there is limited evidence for their efficacy, largely due to poor research studies.

Subjective Experiences of Medication

Gibson et al (2004) noted the need for qualitative research to be employed alongside the “gold standard” of the “randomised, double-blind placebo controlled trial”. They argued that such information would:

Give an improved understanding of the experience of people with dementia

Improve the relevance of outcome measures if used alongside the “gold standard” trials

Improve understanding around issues such as compliance and user involvement that would be of benefit.

Rawlins (2008) noted that NICE had realised their need to explore this area more fully. In light of your reflections in Activity 5.13, it is clear that a more fundamental shift is needed to see people with dementia as being equal partners in their own care, rather than as objects to be treated (when KItwood’s (1997) idea of “objectification” is being employed – either consciously or unconsciously).

NICE/SCIE (2007) note in their guidance that this information is not of a suitable standard to be relevant at the present time.

|

|

Psychological Interventions |

When considering psychosocial interventions for people with dementia, it is important to consider your purposes for their usage. A framework was proposed by Garret and Hamilton-Smith (1995) that provides a guide for planning therapeutic care. They referred to it as the ELTOS model, which is an acronym that stands for “Enhanced Lifestyle Through Optimal Stimulus”. This model emphasises the following:

Communication: focus on the person rather than the tasks to be performed; and get to know the person in your care

Validation: do not make value judgements when you interpret the actions and thoughts of the person

Lowered stress: remove or minimise stimuli that cause obvious distress to the person

Positive stimulus: build a meaningful activity programme that is based on your knowledge of the particular person and that promotes choice

Teamwork: never underestimate the collective knowledge of the various members of the team pertaining to the person

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.14: QUESTION |

Consider a client you work with who is diagnosed with dementia.

In what way is the ELTOS framework helpful in enhancing the life of the person with dementia?

In what ways can the various facets of the ELTOS model be utilised in a daily planned routine to improve the well-being of the person with dementia?

Communication

Validation

Lowered stress

Positive stimulus

Teamwork

As well as frameworks for psychosocial interventions such as the ELTOS model, there are numerous specific psychosocial therapies that have been developed for working with people with dementia.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.15: QUESTION |

Consider clients you work with who are diagnosed with dementia.

What psychological interventions are employed at present?

What possible psychological interventions could be employed for people with dementia?

Traditionally, there were three psychological interventions that were employed with people with dementia:

Reality Orientation Therapy (Folsom 1968; Holden and Woods 1995)

Validation Therapy (Feil 2002)

Reminiscence Therapy (Coleman 1986; Bornat 1994)

Reality Orientation

Reality Orientation (RO) is said to have originated with the work of Folsom in 1958, when he developed an “aide-centred activity programme for elderly patients” at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Topeka, Kansas (Holden and Woods 1995). During the 1960s, reports began to appear about this approach (for example, Folsom 1968), and the first report of its use in the United Kingdom was published in 1975 (Brook et al 1975). Its aim is to provide information that will orientate the person with dementia to time, place and/or person (Haddad 2009). RO comprises three elements: firstly, the small group; secondly, the informal, one-to-one work; and, finally, “attitude therapy” (Grasel et al 2003)

The small group work: this is variously described as “group RO” or “formal RO” (Holden and Woods 1995). It usually comprises a small group of about six people with dementia. Its form is structured and usually coordinated and led by a member of the staff team. They usually commence with the group introducing themselves to the rest of the group (orientated to person) and then various activities will occur that have the express aim of orientating the person to the present reality (for example, discussing a topical piece of news from that day’s newspaper).

Next, there is the individual work. This element goes by names such as “24-hour RO” or “informal RO” (Holden and Woods 1995). This form of RO is a continuous and ongoing attempt to orientate the person to his or her environment through such means as a mounted board that displays the correct day, date, month and year, and clear signs that indicate where places can be located (for example, the kitchen, toilet, dormitory, etc).

The final element, termed “attitude therapy” refers to the attitude of all carers working with the individual with dementia. It is held that their approach should be consistent. Grasel et al (2003) states that this attitude should be marked by:

Being friendly

Being businesslike

Being polite

Being direct but not imperious

Woods and Holden (1995) note that the prescribed attitudes of those working with people with dementia utilising RO as their approach should display:

Kind firmness

Active friendliness

Passive friendliness

Matter of fact attitude and no demand

They also note that these traits are chosen with reference to the individual’s particular personality and need.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.16: QUESTION |

Consider a particular client you work with who is diagnosed with dementia.

Utilise some of the principles of RO in your daily practice with them (for example, orientating them to who you are, where they are, maybe the day/time if appropriate).

What are some of the effects (positive and/or negative) of RO for:

The person with dementia?

You?

One of the criticisms made of RO is the basic premise of bringing the person with dementia into our “reality” rather than us, as carers, entering theirs. This can lead to potentially distressing situations – such as reinforcing the losses that the person with dementia has experienced (e.g. the death of a spouse). Morris (1999:26) states that:

“correcting someone and confronting them with their deficits is something to be avoided, particularly when the person with dementia is not acknowledging any difficulty”

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.17: QUESTION |

Conduct a literature review to ascertain the effectiveness of reality orientation when working with people with dementia.

The effectiveness of reality orientation will be considered in detail after the discussion of the various therapies.

Validation Therapy

Feil (2002:9) writes:

“In 1963, after seven years of working with oriented, healthy elderly in community centres, I began working with old-old people that is, people aged over the age of 80, who were disoriented, at the Montefiore Home for the Aged in Cleveland, Ohio. My initial goals were to help severely disoriented old-old to face reality and relate to each other in a group. In 1966, I concluded that helping them to face reality is unrealistic. Each person was trapped in a world of fantasy. Exploring feelings and reminiscing encouraged group members to respond to each other. Music stimulated group cohesion and feelings of well-being. I abandoned the gaol of reality orientation when I found group members withdrew, or became increasingly hostile whenever I tried to orient them to an intolerable present reality”

As such, validation therapy is humanistic in its approach (as it focuses on validating the feelings of the person). It is also based on the developmental theory of Erikson (1980). Indeed, Feil (2002) added an additional stage “beyond integrity” which she named as the “old-old stage”. This stage comprises the task of “resolving of the past” and results either positively (with “resolution”) or negatively (with “vegetation”). Feil (2002) holds that the individual who is disoriented reverts to previous life stages in order to “sort out dirty linen” that needs to be resolved. Feil (2002:19) notes that:

“This is not a conscious move to the past, like Erikson’s sixth and final stage. It is a deep human need: to die in peace”

The people most likely to benefit from the validation approach are those who:

Are old-old, aged 80-100 plus

Have led relatively happy, productive lives

Have denied severe crises throughout their lives

Hold onto familiar roles

Show permanent damage to their brain, eyes, ears

Have diminished ability to move, control feelings, remember recent events

Meet their human needs for love, identity, and expression of feelings by using body movements and images learned early in life

Have unresolved emotions they must express

Choose on a subliminal level of awareness to retreat, to avoid painful present-day reality

Are in the Resolution versus Vegetation stage of life, recalling the past in a struggle to resolve it. They are resolving until death

The principles of validation are summarised by Feil (1992:44) as behavioural principles, developmental principles, and psychological principles.

|

Table 5.3 Validation Principles |

||

|

Behavioural |

Developmental |

Psychological |

|

Early learning stays Event in the present can trigger a past memory Physical loss in the present can trigger a vivid memory of an early emotion |

Each stage in life has a different task, which is rarely resolved The old-old enter a final stage (Resolution v Vegetation) and have problems expressing unfinished tasks Physical losses help the old-old blot out the present and restore the past |

Ignored feelings fester If exposed, they lose their power Listening with empathy relieves the emotional burden Ignoring the emotions of the old-old does not result in a modification of their behaviour – it worsens or they withdraw! |

Feil (1992) categorises this final state as comprising four stages that have certain physical and psychological characteristics: malorientation, time confusion, repetitive motion and vegetation. In order to engage in validation as a psychological approach, the practitioner must engage in three steps: firstly gather information (it is important that you know as much as you can about the individual); secondly, assess the stage of disorientation (as this will dictate which validation techniques you will utilise); and, finally, meet the person regularly and employ validation techniques (which are stage-specific).

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.18: QUESTION |

Consider the following scenario:

Mrs Jones is severely confused and is attempting to leave the unit. She would be at risk if she wandered outside the care setting unescorted. When asked why she wants to leave, she says: “I must go home to see my mother. She hasn’t been very well and needs me to cook her some supper.”

What would be your response if you utilised principles of:

Reality Orientation?

Validation Therapy?

A useful comparison of the two approaches is given by Day (1997) when she notes the basic tenets of validation therapy and reality orientation.

|

Table 5.4 |

|

|

Validation Therapy |

Reality Orientation |

|

|

Clearly, when these tenets are applied to the case of Mrs Jones above (Activity 5.18), there are implications for her well-being as noted by the possible responses to the following:

“What was your mother like?” versus “You are in hospital”

“You must care about her greatly?” versus “Your mother died a long time ago”

“How are you feeling?” versus “You are too much of a risk if you leave the unit”

“Come and sit down and tell me about her” versus “You are in your eighties; how old would that make your mother?”

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.19: QUESTION |

Conduct a literature review to ascertain the effectiveness of validation therapy when working for people with dementia.

The effectiveness of this psychosocial intervention will be discussed later.

Reminiscence Therapy

The third type of traditional approach to working with people with dementia is reminiscence therapy. Problems of definition abound with this therapy as the terms reminiscence and life review are sometimes used interchangeably, and sometimes used to refer to specific and distinct approaches. Haight and Burnside (1993) state that life review refers to the approach utilised by professionals when they seek to assist the person gain a sense of integrity. This view is shared by Garland (1994), and is more of a one-to-one psychotherapeutic approach that involves the person working through often quite painful memories. Reminiscence, by contrast, is usually more of a group process that has, as its main aims, such things as socialisation, communication, and entertainment. As such, it owes less to psychodynamic therapeutic approaches. However, it is probably best to consider these as a continuum with reminiscence being at one end of the spectrum and intensive psychodynamic life review being at the other end (see the descriptions of reminiscence offered by LoGerfo 1980 below).

Originally, this approach was utilised with non-cognitively impaired older adults as a means of getting them to review their lives (Coleman 1986). This grew out of the observations by Butler (1963) that life review was a natural part of the ageing process and not a symptom of mental illness. Interestingly, the recall of autobiographical memories usually is related to the early adulthood stages of a person’s life, that is, between the ages of ten to thirty (Rubin et al 1998).

LoGerfo (1980) has argued that there are three types of reminiscence therapy:

Simple or informative reminiscence: the non-conflictive type of reminiscing that is performed informally and results in joy and an increase in self-esteem and personal identity (for example, Atkins (1980) points out the coping function of simple reminiscence in a funeral context).

Evaluative reminiscence: this is a conflict-resolving form of reminiscence that occurs when the individual is confronted with such things as their own mortality, physical and mental deterioration, and/or the life review process, as discussed by Butler (1963). An example of this approach is when the person begins to take stock of their achievements, and begins to resolve any intra-psychical conflicts. This approach has been shown to show a positive correlation between it and ego-integrity (Taft and Nehrke 1990).

Obsessive-defensive reminiscence: this form of reminiscence is pathological, in the sense that it occurs when intense feelings of guilt and/or despair are unable to be faced by the individual. Interestingly, it can also occur when the environment refuses to let the person confront such painful issues, for example, within an institutional setting (Poulton and Strassberg 1986). This is probably where the ambiguity comes from in differentiating reminiscence from life review as this has close associations with psychodynamic therapies.

Irrespective of the type of reminiscence, its function is the same (Bremers and Engel (1985) cited in Droes 1997: 136):

“to improve intra-personal and inter-personal functioning by means of reliving, structuring, integrating and exchanging memories”

This usually involves the use of certain aids (for example, items from the period in question, smells that are reminiscent of the time being discussed, etc). Research into this approach has shown benefits for patients (Berghorn and Schafer 1987; Woods et al 2005) and staff (Head et al 1990; Moos and Bjorn 2006). Both groups of people interacted more, and the older adults felt valued.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.20: QUESTION |

What are some of the issues that need to be considered before utilising reminiscence therapy with your clients?

Factors which have been shown to be beneficial for the therapeutic effect of reminiscence therapy to be achieved have been defined by Bloch and Crouch (1985) as:

Catharsis: expressing strong emotions about an event/situation and, as a result, appearing more relaxed afterwards

Self-disclosure: revealing personal information not previously known to the group members

Being more open: experimenting with alternative ways to express and relate to others

Universality: the realisation that you are not alone

Acceptance: feeling accepted and secure in the group

Altruism: helping each other as and when required

Guidance: giving advice or information to a member (or members)

Self-understanding: members display new insights into their sense of self and/or their relationship to others

Vicarious learning: learning occurs by observing other members (their views, behaviours or the strategies they employ)

Installation of hope: optimism is expressed either with regard to progression within the group or in life more generally

Bender (1995) added another therapeutic factor:

Agency: members express ownership for their actions (either past or present) – although this excludes depressive self-blame

Before utilising reminiscence therapy with people with dementia, it is important to ascertain as much information about the past as possible. Often, the choice of topic can have potentially devastating consequences. For example, consider the following example:

Alan attends your day unit for the first time. He has pre-senile dementia. He attends the reminiscence group led by the occupational therapist who, today, being the day after Remembrance Sunday, is leading the group in reminiscing about the war. After only a few moments, Alan bursts into tears and leaves the room.

This situation resulted because Alan, unbeknown to anyone on the unit, had lost his father in the war. Thus, it is important to consider the emotions that may be elicited as a result of the reminiscence topic for particular individuals within the group. Again, getting to know the person is essential.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.21: QUESTION |

The importance of getting to know the person has been stressed throughout these three traditional psychosocial approaches to people with dementia.

Devise a “Getting To Know You” Sheet that could be utilised for people you work with in order to gather information that would be pertinent to working therapeutically with them.

In a study conducted to evaluate reminiscence and life-review work with people with dementia, Woods et al (1992) devised a “General Life-Course Trajectory” for the interviewers to utilise with the participants. This lists topic areas that would be useful information for anyone working with a person with dementia. They include aspects from the lifespan (birth, childhood, adulthood), relationships (at school, with peers, with family members and friends), work and leisure activities (pets, favourite activities), as well as aspects of their personal life (courting, significant losses, holidays, beliefs and values).

This list of topics is by no means exhaustive, but having such information about the person would go a long way to knowing something about them that may cast light on what they say and how they behave in certain circumstances.

However, the question remains, in this era of evidence-based practice, what is the evidence that reminiscence therapy actually benefits people with dementia?

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.22: QUESTION |

Conduct a literature to ascertain the efficacy of reminiscence for people with dementia.

The efficacy of reminiscence will be discussed below.

Other Therapies

At the present time, there are more therapeutic activities that can be employed for people with dementia than ever before (Brooker 2001). For example, Droes (1997) notes that there are: psychotherapies (supportive, insight-orientated, cognitive-behavioural) psychomotor therapies (movement-oriented methods and body-orientated methods), behaviour modification, remotivation therapy, resocialisation therapy, reminiscence therapy, reality orientation, activity groups (art, cooking, music, dance, for example), and validation. To this list could be added: complementary therapies (e.g. aromatherapy), environmental manipulation, cognitive stimulation and multisensory stimulation, simulated presence therapy and animal-assisted activity (James and Fossey 2008; Fossey 2008).

There have been many studies conducted into the various psychosocial interventions employed with people with dementia. Their limitation has often been caused by either limited numbers of people studies, or poor research designs, that have left findings difficult to generalise about and/or interpret.

|

Table 5.5 |

|

|

Therapy |

Systematic Review Findings |

|

Reality Orientation (Spector et al 2000) |

“The effectiveness of classroom reality orientation (RO) in dementia was evaluated by conducting a systematic literature review. This yielded 43 studies, of which 6 were randomized controlled trials meeting the inclusion criteria (containing 125 subjects.) Results were subjected to meta-analysis. Effects on cognition and behavior were significant in favour of treatment. The evidence indicates that RO has benefits on both cognition and behavior for dementia sufferers. However, a continued program may be needed to sustain potential benefits. Future research should evaluate RO in well-designed multicenter trials.” |

|

Validation Therapy (Neal and Wright 2003) |

“There is insufficient evidence from randomised trials to allow any conclusion about the efficacy of validation therapy for people with dementia or cognitive impairment.” |

|

Reminiscence (Woods et al 2005) |

“Whilst four suitable randomized controlled trials looking at reminiscence therapy for dementia were found, several were very small studies, or were of relatively low quality, and each examined different types of reminiscence work. Although there are a number of promising indications, in view of the limited number and quality of studies, the variation in types of reminiscence work reported and the variation in results between studies, the review highlights the urgent need for more and better designed trials so that more robust conclusions may be drawn.” |

|

Physical Exercise (Forbes et al 2008) |

“Four trials met the inclusion criteria. However, only two trials were included in the analyses because the required data from the other two trials were not made available. Only one meta-analysis was conducted. The results from this review suggest that there is insufficient evidence of the effectiveness of physical activity programmes in managing or improving cognition, function, behaviour, depression, and mortality in people with dementia. Few trials have examined these important outcomes. In addition, family caregiver outcomes and use of health care services were not reported in any of the included trials.” |

|

Multisensory Stimulation (Chung and Lai 2002) |

“A more vigorous review methodology was adopted in this update. The study of Kragt 1997, reported in the previous version, was excluded because the snoezelen programme only consisted of three sessions, which was considered too brief for a therapeutic intervention. Two new trials were reviewed. Meta-analyses could not be performed because of the limited number of trials and different study methods of the available trials. Overall, there is no evidence showing the efficacy of snoezelen for dementia. There is a need for more reliable and sound research-based evidence to inform and justify the use of snoezelen in dementia care.” |

|

Aromatherapy (Holt et al 2003) |

“Aroma therapy showed benefit for people with dementia in the only trial that contributed data to this review, but it is important to note there were several methodological difficulties with this study. More well designed large-scale RCTs are needed before clear conclusions can be drawn on the effectiveness of aroma therapy. Additionally, several issues need to be addressed, such as whether different aroma therapy interventions are comparable and the possibility that outcomes may vary for different types of dementia.” |

|

Music Therapy (Vink et al 2003) |

“Five studies were included. The methodological quality of the studies was generally poor and the study results could not be validated or pooled for further analyses” |

|

Behavioural Management (Spira and Edelstein 2006) |

“Behavioural interventions targeting agitated behavior exhibited by older adults with dementia show considerable promise. A number of methodological issues must be addressed to advance this research area. Problem areas include inconsistent use of functional assessment techniques, failure to report quantitative findings and inadequate demonstrations of experimental control” |

|

Environmental Modification (Price et al 2001) |

“There is no evidence that subjective barriers prevent wandering in cognitively impaired people.” |

|

Psychotherapies (Teri et al 1997) |

“Results indicate that behavioural interventions for depression are important and effective strategies for treating demented patients and their caregivers” |

|

Creative Therapies (Wilkinson et al 1998) |

“stimulating and maintaining social skills, independence, self-esteem and self-belief through drama therapy may improve quality of life. Drama and movement therapy clearly needs further study and in future considerable thought needs to be given to the range of qualitative and quantitative measures used if it is to be adequately evaluated” |

|

Simulated Presence Therapy (Peak and Cheston 2002) |

“SPT has the potential to be used within any care environment in which people with dementia have attachment needs … However, previous attachment style may be an important consideration” |

|

Animal-Assisted Therapy (Greer et al 2002) |

“live cats had the greatest influence on average subject performance [i.e. verbal communication]” |

As can be seen by this brief review of research into therapies for people with dementia, there is some evidence of their effectiveness, particularly within individual studies. However, the Cochrane systematic reviews of therapies only find evidence of efficacy for reality orientation. The NICE/SCIE (2007) guidelines make the following recommendation when it comes to psychosocial interventions for people in varying stages of dementia:

Mild dementia: NICE/SCIE (2007) accept the comment made by Bates et al (2004:644) in their review of psychosocial interventions with mild dementia:

“The review provides some evidence for the use of reality orientation for people in the milder stages of dementia”

And thus recommends the use of cognitive stimulation (reality orientation)

Moderate dementia: NICE/SCIE (2007:25) state that:

“People with mild-to-moderate dementia of all types should be given the opportunity to participate in a structured group cognitive stimulation”

Severe dementia: NICE/SCIE (2007:172) simply state that:

“Multi-sensory stimulation is most typically used with people with moderate to severe dementia.” However, there is no “gold standard” research available to show its efficacy for people with severe dementia.

Cognitive Stimulation Therapy

The NICE/SCIE (2007) recommend the use of cognitive stimulation therapy, it would be worthwhile exploring this therapy for people with mild to moderate dementia. Cognitive stimulation has been defined by Clare (2008:159) as:

“engagement in a range of group activities and discussions aimed at general enhancement of cognitive and social functioning”

This therapy aims to stimulate cognitive functioning by utilising the principles of reality orientation and some of the methods of reminiscence. As there are several cognitive domains that could be targeted (for example, memory, language, attention, and concentration), it is important to ascertain the needs of the people prior to engaging with this therapy. Spector et al (2003) state that it usually consists of fourteen sessions, held twice a week for seven weeks, and each sessions lasts for around forty-five minutes. They also note that (Spector et al 2003: 249):

“Each session began with a warm-up activity, typically a softball game. This was a gentle, non-cognitive exercise, aiming to provide continuity and orientation by beginning all sessions in the same way.”

Then each session focused on a particular theme. For example, Orrell et al (2005) conducted a study on the use of cognitive stimulation therapy which consisted of the following themes:

|

Table 5.6 Cognitive Stimulation Therapy Sessions |

|||

|

Session 01 |

Childhood |

Session 09 |

Categorising Objects (odd one out) |

|

Session 02 |

Current Affairs |

Session 10 |

Using Objects (reminiscence) |

|

Session 03 |

Current Affairs |

Session 11 |

Useful tips (what our grandmothers knew) |

|

Session 04 |

Using Objects (cooking) |

Session 12 |

Golden expression cards (for discussion) |

|

Session 05 |

Number Game (bingo) |

Session 13 |

Golden expression cards |

|

Session 06 |

Quiz (in teams) |

Session 14 |

Opinions on Art |

|

Session 07 |

Music session |

Session 15 |

Famous Faces |

|

Session 08 |

Physical games |

Session 16 |

Word Completion |

As can be seen from such activities, there is a mixture of reality orientation (for example, discussions about current affairs) and reminiscence (for example, discussing things that their grandmothers would say). Thus, cognitive stimulation therapy appears to marry two distinct approaches:

Reality orientation: focuses on presenting information that will orientate the person with dementia to the present

Reminiscence: focuses on past memories

In truth, reality orientation has frequently utilised some aspects of reminiscence in its more formal form (Holden and Woods 1995). What is different about this approach is that the ultimate purpose is not just about orientating the person to the present, but about maintaining cognitive functioning.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.23: QUESTION |

Consider how you would prepare a cognitive stimulation session for the following groups of people:

a group of men with dementia living in a docks area

a group of ladies who were members of the ATS during the war

a mixed group of people meeting in the wintertime

Each session should include the following (Spector et al 2003):

a group symbol to identify the particular group that is usually put on the RO board

a warm-up exercise that will get the people communicating with each other

a reminiscence activity that will be both relevant to the group and will also be cognitively stimulating (you may wish to include multi-sensory activities)

We have discussed the main psychosocial interventions for working with people with dementia in general. We will now consider specific situations that people with dementia present with, and consider possible interventions that may be employed to help them. NICE/SCIE (2007) name three such examples in their guidelines:

Behaviours that challenge

Working with comorbid emotional disorders (such as depression and anxiety)

Working with the person with dementia at the end of life

|

|

Therapeutic Work: Non-Cognitive Symptoms and Behaviours that Challenge |

Behaviours that Challenge

In Unit Four we considered possible rationales for why behaviours that challenge may present in people with dementia, when we explored behaviour as a means of communicating need rather than a symptom of dementia. There are numerous behaviours that present themselves that could be referred to as “challenging”. For example, with regard to Alzheimer’s disease, Thomas (2008) notes the following:

|

Table 5.7 |

|||||

|

Psychotic |

|

Mood |

|

Behavioural |

|

|

Delusions Misidentifications Hallucinations |

30% 20% 20% |

Depression Euphoria Anxiety |

25% <1% 30-50% |

Apathy Agitation Wandering Aggression: Physical Verbal |

70% 30% 20% 20% 40% |

When related to specific types of dementia, Devan and Lawlor (2000) argue that they appear in the following frequencies:

|

Table 5.8 |

||||

|

Symptom |

AD |

VaD |

DLB |

FLD |

|

Agitation |

+++ |

+++ |

+++ |

+ |

|

Aggression |

++ |

++ |

++ |

+ |

|

Delusions |

++ |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

|

Hallucinations |

+ |

+ |

+++ |

- |

|

Depression |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

+ |

|

Anxiety |

++ |

+++ |

+ |

+ |

|

Apathy |

++ |

+++ |

++ |

++++ |

|

Sexual Disinhibition |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+++ |

By way of example, we shall consider the case of the person with dementia who engages in wandering behaviour. Wandering behaviour is a complex issue and is difficult to define, being variously interpreted in terms of:

Geographical pattern (Martino-Saltzman et al 1991)

Typology (Hope et al 1994)

Neurocognitive deficits (Algase 1999)

A single definition was proposed by Stokes (2000:31):

“Wandering is a single-minded determination to walk that is unresponsive to persuasion: (a) with no or only superficial awareness for personal safety (for example, an inability to return; impaired recognition of hazard); (b) with no apparent regard for others (for example, in terms of time of day, duration, frequency or privacy); or (c) with no regard for personal welfare (thereby disrupting the essential behaviours of eating, sleeping, resting)”

This definition is broad enough to ensure that not all walking behaviour is classified as wandering and, secondly, allows for a multitude of reasons for why the person engages in such acts.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.24: QUESTION |

Consider the potential reasons for why a person with dementia would engage in acts of wandering behaviour.

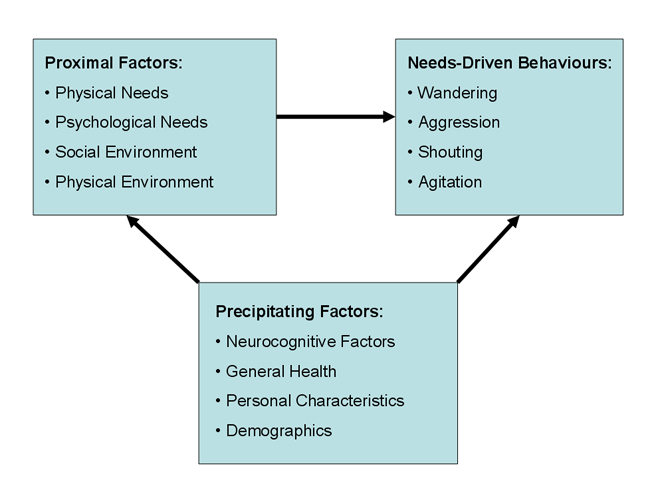

Lai and Arthur (2003) state that a comprehensive assessment is the basis for identifying and developing the appropriate management strategies for people with dementia who engage in acts of wandering. As such, it is important to know why they are wandering before one can seek appropriate interventions. The Needs-Driven Dementia-Compromised Behaviours Model (Algase et al 1996) argues that the so-called “challenging” behaviours that people with dementia engage in are a result of unmet needs.

Figure 5.3: Needs-Driven Compromised Behaviour Model

Hope and Fairburn (1990) proposed a tentative typology of wandering behaviours:

Trailing/Checking: follows carer around for at least thirty minutes

Pottering: walks around trying to do odd jobs

Aimless walking: mobilises with no apparent purpose

Purpose not appropriate: walking that seems inappropriate to carer

Appropriate purpose but excessive frequency: mobilises for a valid reason, but does so too many times

Excessive activity: the person walks distinctly more than normal

Night time walking: mobilising by night

Needs to be brought back home: number of times they are brought back home

Attempts to leave home: attempts to leave house and is prevented

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.25: QUESTION |

Consider the typology proposed by Hope and Fairburn (1990).

How helpful do you find it for your own practice?

What do you like/dislike about this typology?

The typology has been subjected to analysis by Albert (1992), who found that there was not an equal weighting between the nine categories. For example, although more people in their study engaged in “excessive wandering”, the majority of people all engaged in acts of “needs to be brought back home”. This does not allow for a scale to be developed with any degree of accuracy. There is also the issue about etiology of these wandering behaviours. Albert (1992) found little evidence to support some of Hope and Fairburn’s (1990) ideas (for example, checking and pottering being related to feeling afraid). However, the typology does raise important issues about why this behaviour is occurring and, as a result, interventions can be tailored accordingly.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.26: QUESTION |

What interventions do you and/or your unit employ with a person with dementia who engages in wandering behaviour?

There have been many approaches to dealing with wandering behaviour in people with dementia. This is largely reflective of the belief and values of the practitioner (for example, if you believe it has a physiological cause, then you will treat accordingly). As such, treatments such as “liquid cosh” have been employed, in spite of studies that have shown the dangers of using antipsychotic medication with people with dementia (Ballard et al 2009). There are also ethical issues around such interventions as electronic tagging (Hughes and Louw 2002).

So, what works? In their review of the studies concerning interventions for people with dementia who wander, Robinson et al (2007) found twenty-seven papers that met their inclusion criteria. These papers consisted of interventions such as:

Walking

Exercise groups

Music groups

Distraction therapies (for example, carrying out meaningful activities)

Validation

Reminiscence

Reassurance

Electronic devices

Environmental modifications

Massage/touch

Physical restraint

Reality orientation

Collusion

Electronic tagging/ Surveillance

Physical barriers

They found that there was a reduction in wandering behaviours when walking, exercise, aromatherapy, and massage and touch were utilised. There was, however, no evidence to support the use of music therapy and the use of special care units. Finally, they could find no studies for inclusion to ascertain whether such interventions as electronic devices, physical barriers, behavioural techniques (such as reality orientation and collusion) and physical restraint were successful. However, evidence of effectiveness is not the only consideration for an intervention’s usefulness. There are also issues around acceptability and ethics that need to be considered. For example, Robinson et al (2007) found that carers found music therapy “very acceptable”, in spite of the fact they could not ascertain its clinical effectiveness. This may relate to what Pulsford (1996) asked: “Who are we most concerned to help?” (discussed above).

|

|

Therapeutic Work - Specific Situations: Emotional Problems, Pain, and Palliation |

Emotional Problems

Ballard et al (1996) have shown that emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression are common in people with dementia. However, they are often difficult to diagnose. It is vital to ascertain the cause as this is important when considering appropriate interventions. For example, current prescribed medication being taken by the person may exacerbate the emotional problems.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.27: QUESTION |

Consult a copy of the British National Formula, and find out which common medications prescribed for older people could result in exacerbation of emotional disorders. You will find this information in the Side Effects section of the drug entry.

There are many medications that can result in emotional problems for people taking them. These include: psychotropic medications (for example, benzodiazepines and antipsychotics); anti-Parkinsonian drugs (for example l-Dopa and amantadine); antihypertensive medications (for example, propranolol and reserpine). Other medications such as steroids are also listed as having side-effects with the potential of exacerbating emotional problems for the taker. There are also physical health problems that need to be assessed as they are known to contribute to emotional problems. For example, major depression has high prevalence rates in people diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (Slaughter et al 2001), and about one in four people who have a stroke will develop depression (Beekman et al 1998). Due to these two conditions being precipitating factors in dementia, they need to be considered in any assessment of the person with dementia.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.28: QUESTION |

Consider the possible causes of depression for the person with dementia.

It may be helpful to consider possible causes under the following headings:

|

Biological |

Psychological |

Social |

|

|

|

|

Depression can have several causes. For example, Gelder et al (1996) state that it could be the result of:

Genetics/family history

Early development problems (e.g. childhood abuse)

Personality (e.g. neuroticism)

Environmental factors (e.g. stressful life events)

Social factors (e.g. lack of social support)

NICE (2004) produced guidance for depression that was slightly amended in 2007. Although it states that it does not cover depression secondary to a physical and/or mental health problem, the guidance advises the use of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and/or a course of cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) for the person diagnosed with mild to severe depression.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.29: QUESTION |

Consider a person with dementia you work with who experiences emotional problems such as depression.

Are they currently prescribed an SSRI? If so, which one? What are the potential side-effects that need to be monitored?

Do you think that CBT would be of benefit to them?

What are some of the issues to consider when providing an intervention for the person with dementia experiencing depression?

Regarding the person with dementia, there are issues to be considered:

Will another medication increase their chances of falls? (polypharmacology)

Will they remember to take it? (compliance)

What about the side-effects? (e.g. gastro-intestinal problems)

Is CBT appropriate for people with cognitive impairment?

In their review of interventions for comorbid problems in people with dementia, NICE/SCIE (2007:235) state that:

“There is limited evidence from one RCT … that a CBT-based approach may be helpful in treating depressive symptoms in people with AD, and this may also benefit carers who are actively involved in the treatment … There is, however, a lack of information regarding the appropriateness of this approach at different stages of dementia”

Interestingly, they note from their review of qualitative data, that people with dementia value meeting in groups. This may imply that the causes of depression for some may not be decreased levels of serotonin (the biological view of depression), but rather the consequence of unmet psychological and social needs of the person with dementia.

End of Life Care

NICE/SCIE (2007) considers this topic in detail in section 4.11.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.30: QUESTION |

Read section 4.11 of the NICE/SCIE (2007) guidance on dementia pertaining to end of life care.

Make notes of what you learn.

The NICE/SCIE (2007) state the applicability of the information they produced concerning palliative care in general (NICE 2004b) to dementia specifically. This includes the use of three specific tools that, collectively, will be of real benefit to people in the last stages of their lives. The first tool they recommend is the Gold Standard Framework (Thomas 2003). This is an evidence-based approach to assessment and care. It aims to improve and optimise the quality of life for patients, family and friends in the last years of life. It seeks to achieve this by improving the seven “Cs” of:

Communication

Control of symptoms

Continuity of care

Coordination

Care support

Care of those who are dying

Continual learning

The second tool recommended by NICE/SCIE (2007) is the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) for the dying patient (Ellershaw and Wilkinson 2003). Originally developed as a tool to enhance education and training for people working with the dying, it now incorporates an integrated care pathway to structure such care. It begins by noting the signs and symptoms that identify a person who is dying. These include such things as: the patient is bed-bound, semi-comatose, only taking sips of fluids, and has problems taking oral medication. If two or more of these criteria are met, then the LCP can be implemented. The first thing it seeks to do is review all currently prescribed medication. It discontinues non-essential medication and prescribes medication to address current symptoms. This ensures that a framework is in place for good quality end-of-life care (Buckley 2008).

The final tool that NICE/SCIE (2007) recommend is the Preferred Place of Care Plan (Storrey et al 2003). Although health policy states that people who are dying should be able to die in a place of their own choosing (DH 2000), only 20% of us actually do (NCPC 2003). The Preferred Place of Care plan consists of four sections:

Family profile: outlines who the key carers will be

Patient’s and Family’s understanding of the diagnosis and possible outcomes are documented (including advanced directives)

A comprehensive assessment of health and social service involvement

A variance sheet to outline any changes to the care plan

This care plan has two provisos: the first is that the person can change his or her mind at any time throughout the care being given; secondly, some choices may not be honoured (for example, if a carer becomes ill, or there is a lack of resources). Research is being undertaken to compare such care plans with actual care and to ascertain if people’s wishes are honoured and met.

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.31: QUESTION |

Reflect on your practice with people with dementia at their end-of-life.

How does it relate at present to these recommendations?

The care of the person with dementia at the end of life offers challenges to all concerned (Peacock 2008). These include issues for:

The informal carers: difficulties in decision-making

The formal carers: lacking autonomy to act

The person with dementia: is he or she receiving the best quality of care available?

It also consists of challenges to do with treatment. This is partly the result of different care regimes for people with cancer and those with dementia (Robinson et al 2005), and partly the result of the purpose of care – to improve life years or improve quality of life for the person with dementia is an important issue to consider. For example, Shah (2006) illustrates some of the issues by considering the case of an 85-year old male with Alzheimer’s disease and cancer. He notes the discussion surrounding the use of PEG feeding for this individual:

The children felt he was starving to death

The nurses felt he was at risk of aspiration

The medics consulted felt it was inappropriate (due to no signs of aphagia)

Shah (2006) concludes that there is no evidence of improved nutritional status nor decreased risk of aspiration for the person with dementia to have a PEG in situ. Such findings have been around for at least the last decade (see Finucane et al 1999), and yet there are still cases of people with dementia having PEGs inserted (Braun et al 2005). It is clear that the overriding motivation for PEG feeding is to “improve life years”.

It would be useful in a consideration of palliative care to distinguish three things:

What is meant by palliative care?

What are the needs of people with dementia requiring palliation?

How can these needs best be met?

What is Palliative Care?

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.32: QUESTION |

What do you understand by the term “Palliative Care”?

In what way is palliative care applicable to dementia care?

According to Addington-Hall (1998), palliative care can best be considered as a continuum: at one end, the approach comprises good quality, person-centred dementia care; whilst, at the other end, there is the specialist care required in the terminal stages of the illness. However, as Becker (2009) notes:

“The transition point between curative interventions designed to maximise health and those that are more palliative-oriented is never easy to define in any care environment. It represents one of the biggest challenges all healthcare professionals face in clinical practice”

According to the World Health Organisation (2002:84), palliative care is:

“an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual”

One of the difficulties of applying this definition of palliative care to dementia care is that of conceptualising dementia as a “life-threatening illness”. However, if palliative care is seen in terms of a continuum, as Addington-Hall (1998) notes, then there are clear links between the two. Hughes et al (2007) ask whether specific aspects of dementia care should be incorporated into palliative care at all. They respond by stating that (Hughes et al 2007: 251):

“A reasonable response might be that if conceptual packaging in this way leads to improvements in patient care, perhaps through advance care planning, then the enterprise would seem worthwhile”

Palliative Care Needs of People with Dementia

|

|

ACTIVITY 5.33: QUESTION |

Consider a person with dementia you have worked with in the last stages of their illness.

What needs did they have?